There’s More to It Than You May Think

Introduction

Calibration labs frequently need to certify the average roughness (Ra) of calibration specimens or samples. This seemingly straightforward task, however, involves more than running a roughness gage across the surface and reading the Ra value.

Variations in basic settings can result in Ra values that differ by orders of magnitude.

To properly measure and report average roughness, we need to establish measurement protocols to ensure that the value is measured accurately and that it is measured the same way every time, both in the calibration laboratory and by the customer.

Measuring Roughness

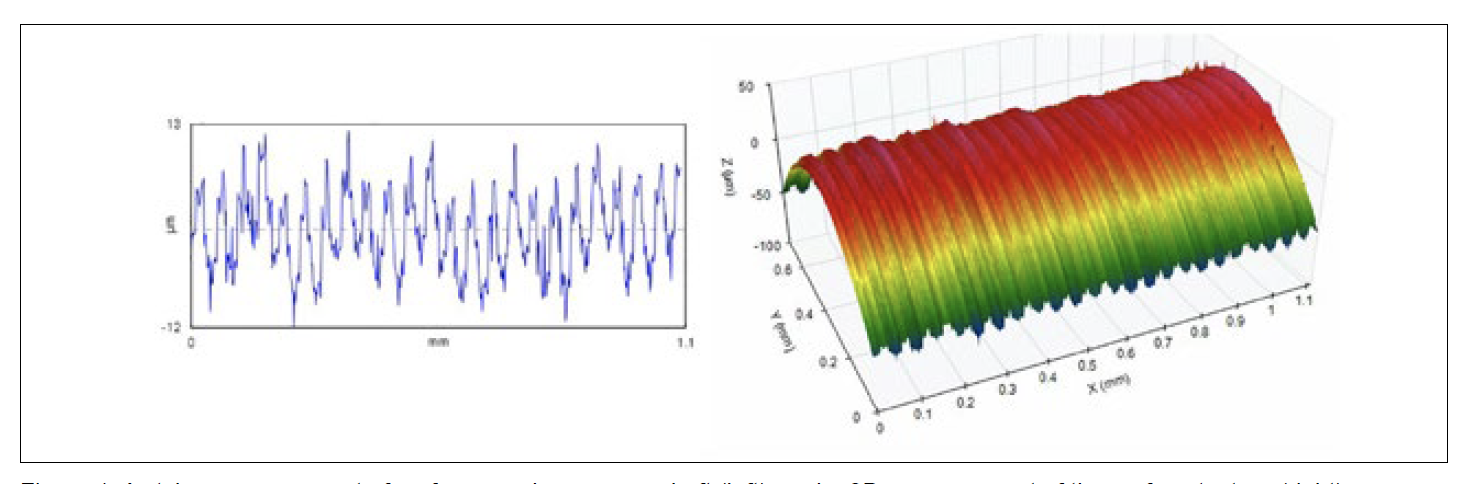

Stylus-based roughness gages are the most widely used instruments for measuring surface texture. These systems measure texture by moving a fine, diamond stylus across the surface. The stylus follows the surface texture, rising and falling to create a two dimensional “profile” (Figure 1, left). Non-contact, optical measurement systems producing 3D texture data (Figure 1, right) are becoming more prevalent in industry and laboratories as well for these types of measurements.

While these systems are designed to accurately measure texture, there are many factors that go into calculating parameters such as Ra based on those measurements. Differences in these factors will dramatically influence the parameter values.

In order to discuss these factors, however, we first have to go back to basics and discuss how we define “roughness.”

Surface Texture Consists of Roughness, Waviness, and Form

As measurement equipment and software have advanced, our understanding of surface texture has developed as well. Rather than thinking of a surface as having a generalized “roughness,” we now more properly describe a surface’s “texture,” and the range of features of varying sizes within that texture (as well as spacings, directionality, etc.).

Figure 1. A stylus measurement of surface roughness on a shaft (left), and a 3D measurement of the surface texture (right).

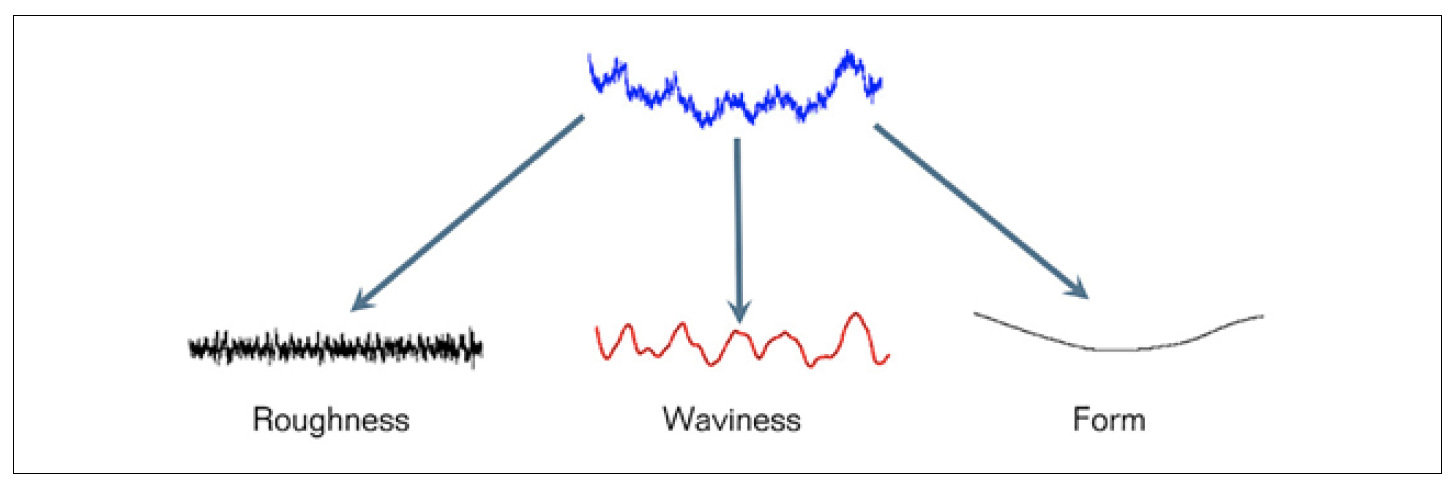

Figure 2. Surface texture consists of roughness (left), but also waviness (center) and form error (right). Depending on the application, it may be important to control all three bands. Image courtesy The Surface Texture Answer Book [1].

We describe the size of the surface features in terms of “wavelengths,” from short-wavelength roughness to longer-wavelength “waviness” and “form error” (Figure 2).

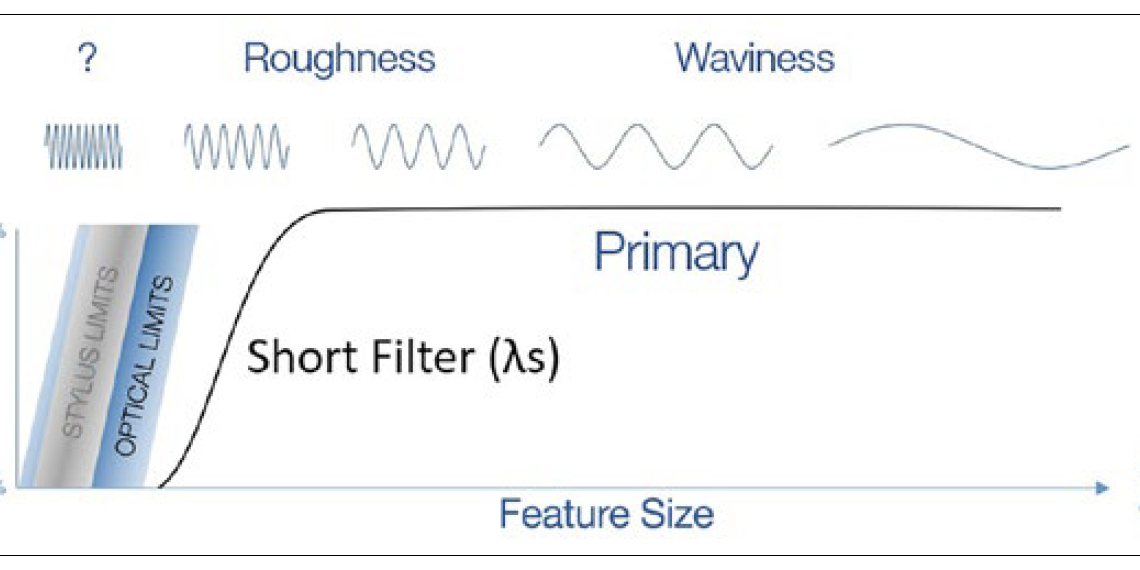

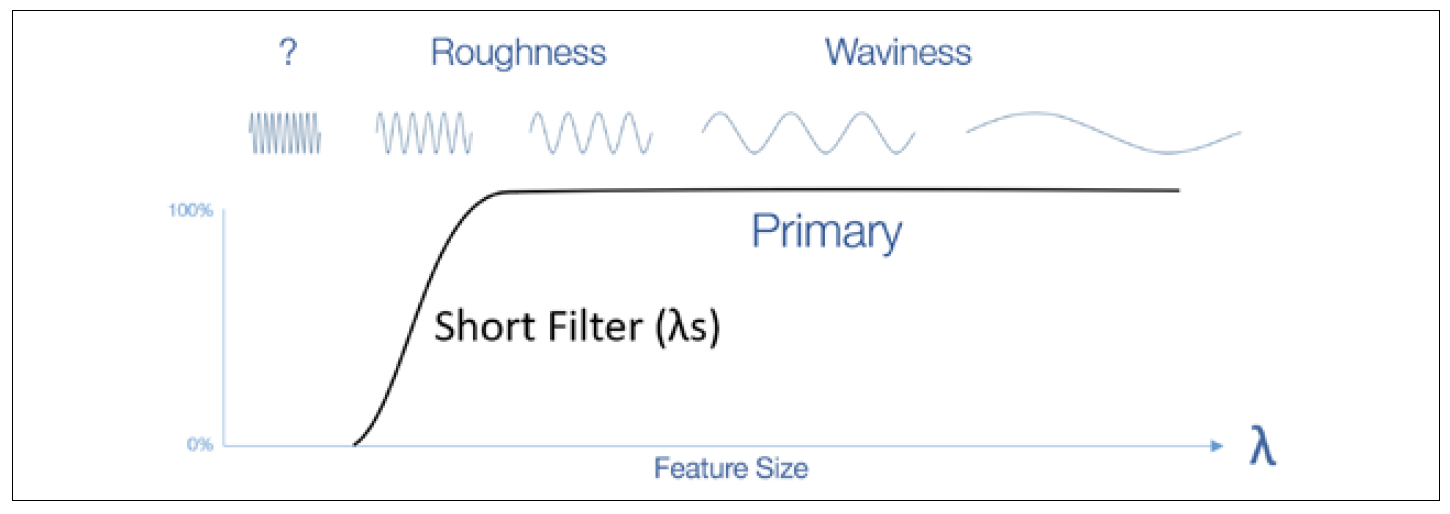

The raw measurement of a surface will contain the full spectrum of wavelengths extending from microscopic (even atomic) scales too small to be resolved by the instrument, to progressively larger roughness, waviness, and overall form (Figure 3).

“Roughness” Refers to a Band of Feature Sizes

The size of the features we call “roughness” is not based on standardized values. Instead, the range is determined by the size of features that matter for the application. On a polished mirror, we may define “roughness” as features that scatter light. Those

feature sizes, however, would be orders of magnitude too small to matter for a machined surface. At even larger scales, we may define the roughness of a road based on the large features that make a car bounce via the shock absorbers.

Depending on the application, the longer wavelength waviness may be as important as

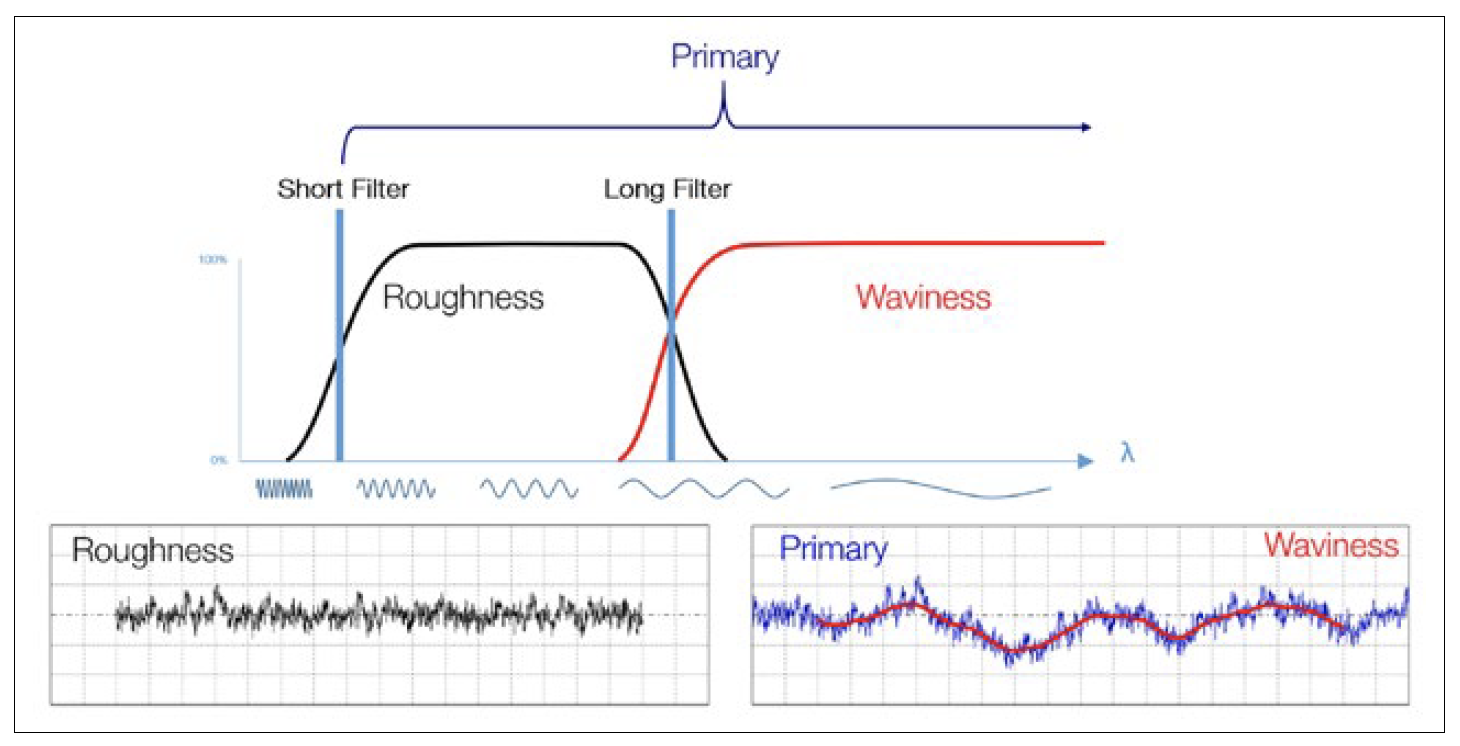

the roughness for controlling noise, sealing, fit, appearance, etc. To analyze texture, we use a series of “filters” to define a roughness band (and waviness band) for the particular surface. These filters attenuate smaller or larger wavelengths so that we can accurately assess the features we know matter for the application. These filters are not optional; they are required to provide a repeatable basis for the parameters (as we will see in the following, changing these filters can result in huge variations in measured values).

Defining the Roughness Band

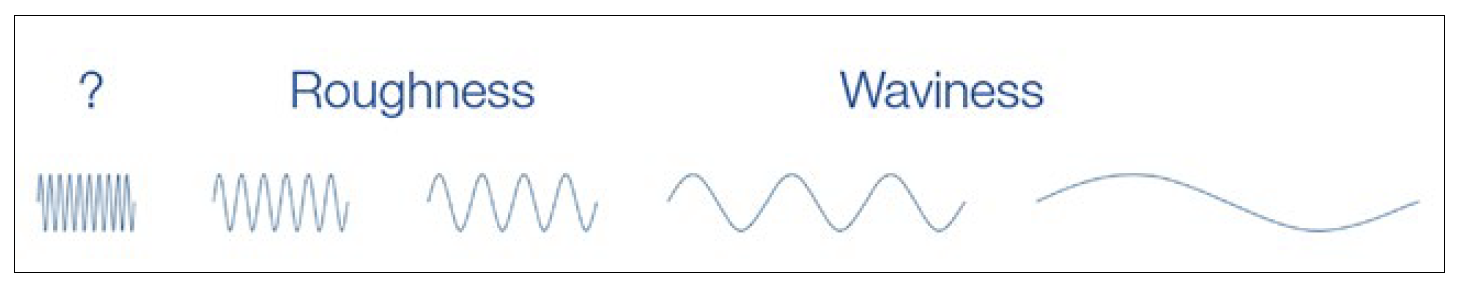

To establish the roughness band of wavelengths, we first remove the overall, dominant shape of the surface (tilt, cylinder, etc.) from the measured data. Next, we define a lower limit of the roughness band. The Short (or “S”) Filter defines the smallest features we will consider to be “roughness” for the application (Figure 4). The Short Filter attenuates wavelengths smaller than the filter wavelength (λs); they will not be included when we calculate roughness parameters such as Ra. The remaining data is called the Primary Profile.

Figure 3. Surface texture consists of a spectrum of feature sizes and spacings.

Figure 4. The Short Filter defines the smallest features to include when calculating roughness parameters. Image courtesy The Surface Texture Answer Book [1].

Next, we apply a Roughness Filter (also called the Long or “L” Filter) to define the largest features to be considered as roughness (Figure 5). Applying the Long Filter results in two profiles: the Roughness Profile (which includes the finer roughness features) and the Waviness Profile (consisting of the larger, “bumpier” features).

Roughness parameters, such as Ra, are calculated based on the Roughness Profile, while waviness parameters are based on the Waviness Profile.

Changing the Filtering Will Dramatically Impact Roughness Values

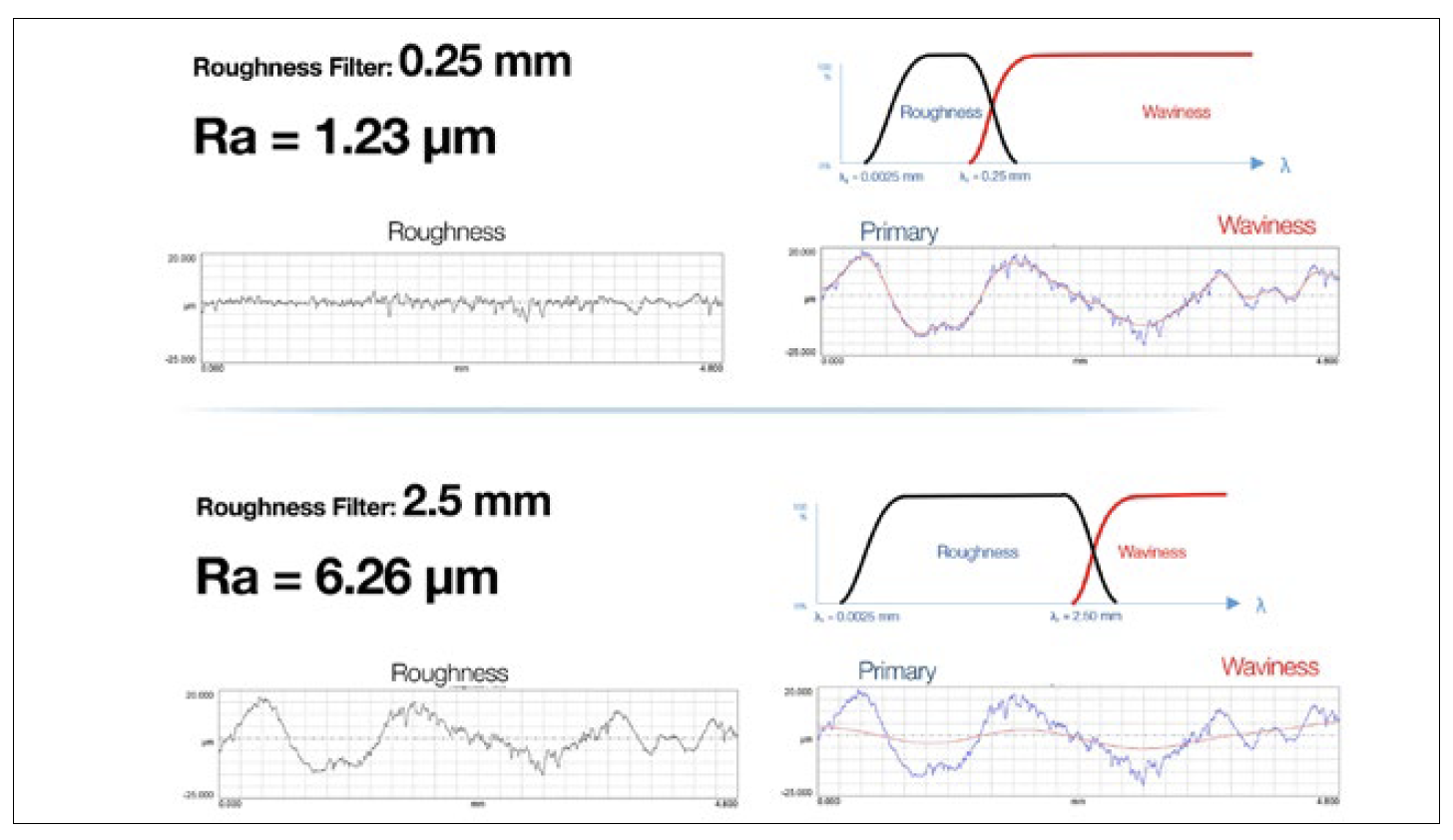

As we mentioned above, changing the roughness filter’s cutoff wavelength will impact which feature sizes are included in the roughness and waviness profiles. This will, in turn, affect the roughness and waviness parameter values. Figure 6 shows the impact of changing the roughness filter’s cutoff wavelength from 0.25 mm to 2.5 mm. With the larger cutoff value, more of the “lumpy” features are included in the Roughness Profile, resulting in an Ra value nearly 6 times larger! It’s critical to know how to verify/adjust the filter settings for your instrument and analysis software in order to produce meaningful parameter values.

Specifying Filter Cutoffs

When roughness values are required, the filter cutoffs must also be specified. Despite this

requirement, however, the values are not always stated, particularly on older drawings. Calibration patches, for example, may be marked with a target Ra value but may not indicate the roughness range that was used to reach that value. When filter cutoffs are not specified, the best option is to contact the person responsible for the surface design. When this is not possible, the major standards that govern surface roughness provide tables. For random surfaces, we use the Ra value and Table 3-3.20.2-1 in the ASME B46.1-2019 standard. For periodic surfaces (sine wave, sawtooth, etc.), we use the Rsm value (the mean of the roughness profile feature widths) described in ASME B46.1-2019 Table 3-3.20.1-1. These filtering selections must appear on the certificate that the calibration lab provides with the results.

Considerations for Measuring

Roughness In addition to the filter settings, other aspects of texture measurement need to be specified in order to produce repeatable roughness parameter values.

Instrument Type

As we mentioned above, the most common instruments for measuring surface roughness

are stylus-based instruments and 3D optical instruments. All measurement technologies have unique characteristics that may not correlate to other technologies. A measurement protocol should define the type of instrument to use, to ensure repeatable results.

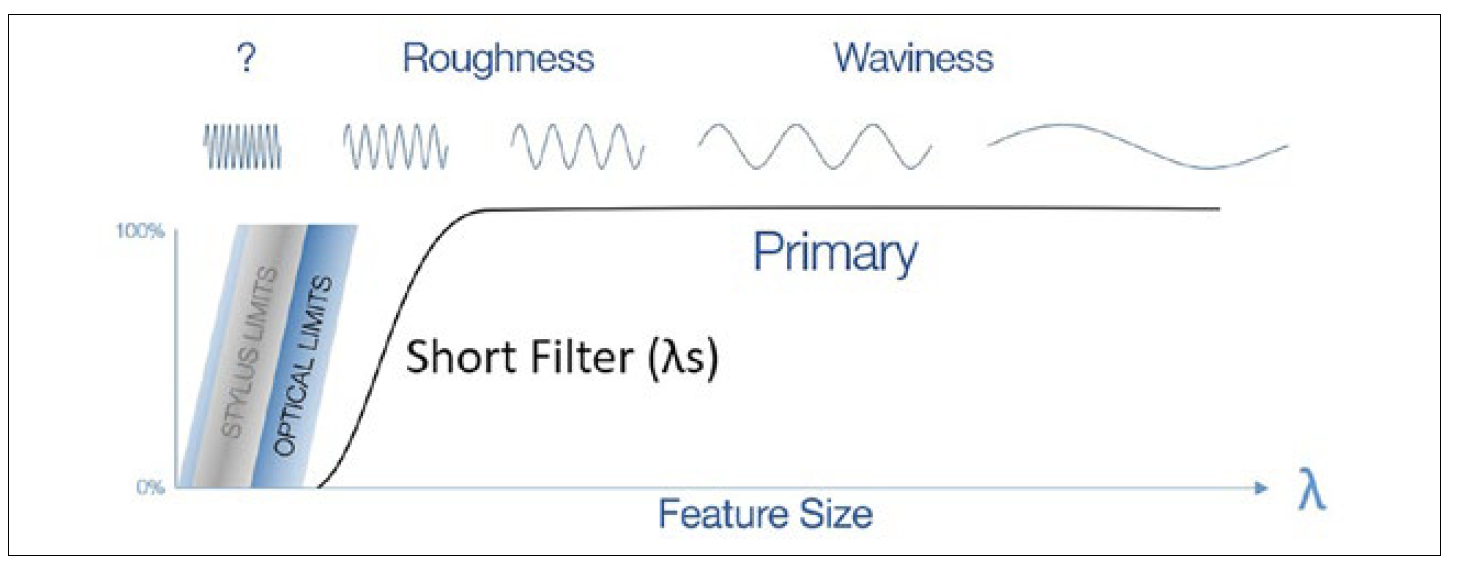

Instrument Resolution

All measurement systems have a limit to the smallest features that can be resolved (Figure 7). The limits will be based on the measuring instrument itself, but also on the choice of stylus probe (on a profilometer) or objective (on an optical system). Be sure that the system as configured is able to measure beyond the features specified by the Short Filter. This way the wavelength band is defined mathematically, rather than by physical properties which can vary from system to system.

Figure 6. For this surface, changing the Roughness Filter cutoff from 0.25 mm to 2.5 mm results in a 6X change in the Ra value.

Figure 7. Choose a measurement system that can resolve the smallest feature sizes specified by the short filter.

Probe size

A stylus profilometer can use different stylus probe tips, with 2 μm and 5 μm radius tips being the most common. The 2 μm tip, however, may resolve finer features, and therefore measure a different profile, than a 5 μm tip. The Short Filter must be selected with the stylus tip radius in mind. For example, a 2.5 μm Short Filter is meaningless if the data has

already been mechanically “filtered” with a 5 μm stylus tip radius. ASME and ISO standards generally recommend a 2 μm tip radius for the majority of the surfaces we encounter.

Measurement Speed

The speed at which the probe moves over the surface will also impact which features can be measured. A slower-moving tip can more accurately trace small valleys and sharp peaks. Again, the correct speed should be part of an established measurement

protocol.

Sample Quality

On a scuffed or dirty calibration patch, measuring Ra in different locations and directions may produce very different results. Traversing deep scratches versus measuring parallel to the scratches will provide grossly different Ra values.

Analysis

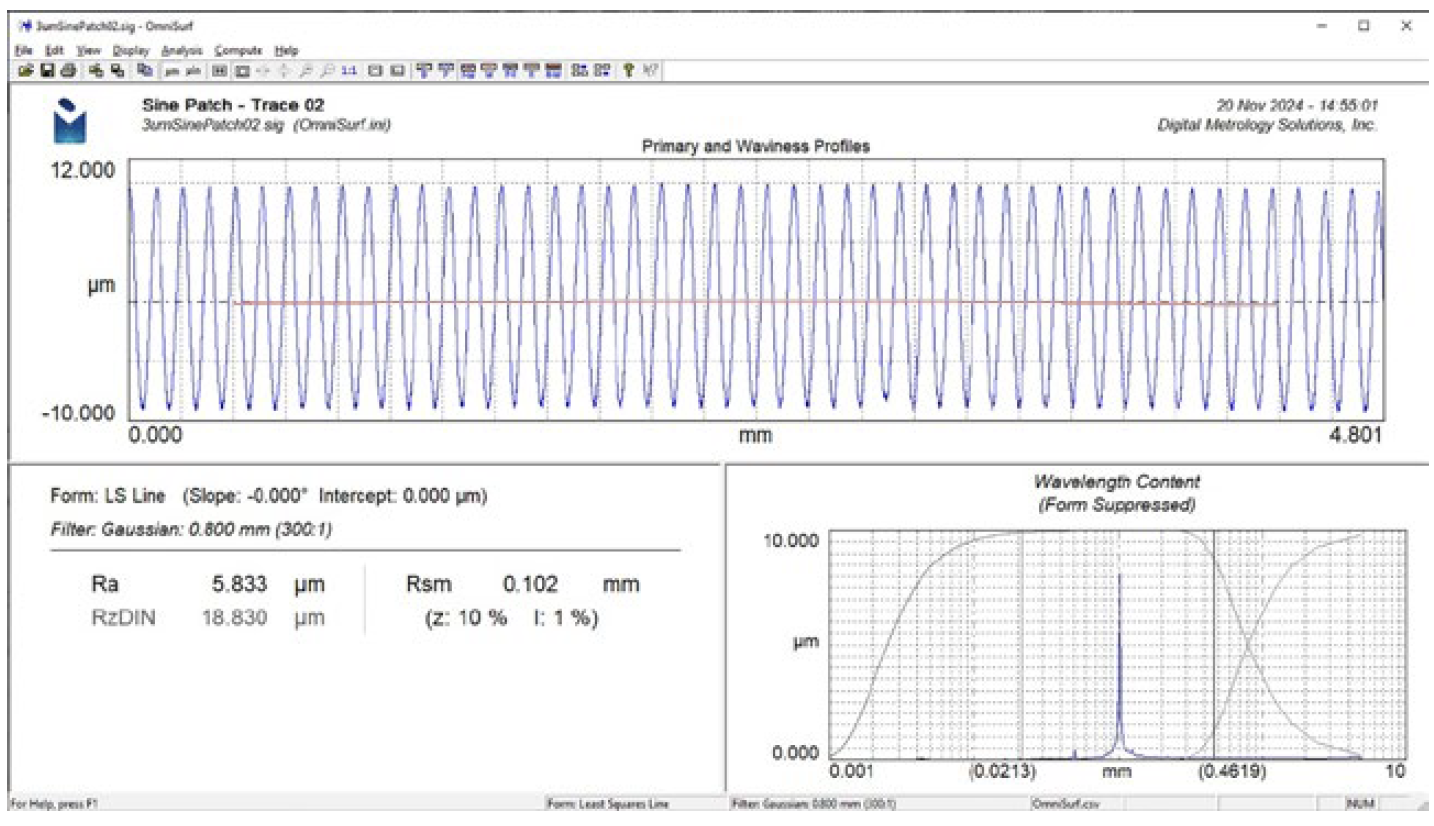

Most surface texture analysis software will calculate basic surface parameters such as Average Roughness. Some software also shows the profile data or even allows the user to interact with the data to understand the effects of various settings (Figure 9). Seeing a surface often gives far more information about the texture than a list of parameter values.

Figure 8. The location and direction of measurement on this calibration patch can produce vastly different Ra values.

Figure 9. Analysis software that provides the ability to see surface texture provides greater understanding than a list of numerical values. OmniSurf software courtesy Digital Metrology Solutions.

Going Beyond the Certificate

The numerical value of Ra does not fully describe the shape of the measured surface. Thus, it is often preferred to provide the raw, measured data files along with the certificate. This allows the customer to load the data into analysis software to see the actual shape of the surface and visually track any changes over time. Various software tools are available for analyzing surface texture datasets, such as the OmniSurf software1 shown in Figure 9.

Learning More about Surface Texture

The world of surface texture goes far beyond a single number definition. To produce quality surfaces, we need to be able to see and understand what matters about the texture for the application. Many resources are available to learn about surface roughness/texture, including short videos, tutorials, books, and sample data available through digitalmetrology.com.

References

[1] Musolff, C. and Malburg, M. The Surface Texture Answer Book. June 2021. ISBN-10: 1736846825.

About the Authors

Mike Zecchino (mzecchino@digitalmetrology.com) has been creating resources and technical content related to measurement and surface texture for over 20 years. His articles have appeared in dozens of publications, and his training materials and videos

support numerous measurement instruments and technologies. Dr. Mark Malburg (mcmalburg@digitalmetrology. com) is the president of Digital Metrology Solutions.

With over 30 years in surface metrology, he is the chief architect of a range of standard and custom software for surface texture and shape analysis.

Dr. Malburg has consulted in numerous industries ranging from optics to aerospace. He is a frequent participant in standards committees and has helped shape many of the standards that govern surface specification and control.